Losing Your Idealism

Despite that all, I’d always been secretly starry-eyed over humanity.

These days, you’re more likely to find me watching an intellectual foreign film than the latest blockbuster, but I still swoon over The Terminator and Batman because these are–at their core–fundamentally human stories. And not just stories about humanity, but truly wonderful battle hymns of the beauty and the essential capacity for goodness of humanity. I’ve learned to operate in shades of grey–every story has a backstory; rarely is there a true “good guy” and “bad guy” in real life–but that is not my natural predilection. I want things to be black and white, wrong or right. And in some ways, I’d still been able to hold onto that.

I’m American by birth, so you know, Nazis are the devil. They aren’t even spoken of as individual humans, but as a sadistic, shared-brain group of pure evil. Their crimes against humanity were always described in vaguely horrific ways. And despite having been taught that from the moment I began schooling, I had at best blurry, unfocused ideas of WWII and all the crimes occurring before, during and after it. No one in my family was killed or maimed in WWII. All my ancestors were in America years before war rumbles began. In other words, I couldn’t begin to understand it.

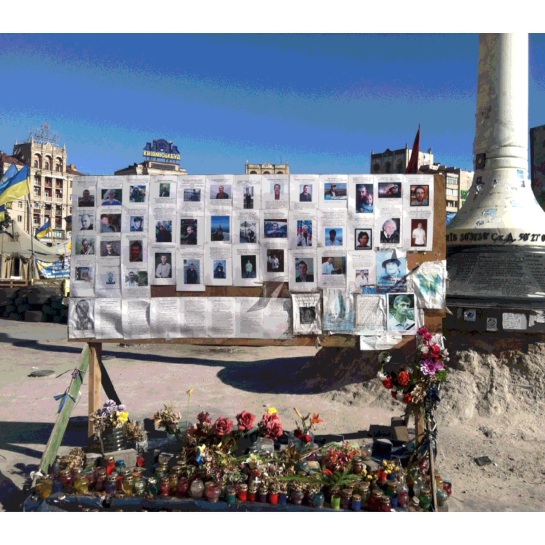

While in Ukraine, I visited both the Chernobyl museum and the museum of the Great Patriotic War (WWII). And in Budapest, I visited the former prison and torture cells that are now part of a museum appropriately titled The House of Terror. These museums–with their graphic imagery, artistically emotive exhibits and chilling statistics–shook me to the core. I left each of them with less understanding of why anyone would want to start a war, and more understanding of the ugly brutality of war. But it was the people I met and came to care for that disturbed me the most. I was there when a dear friend of mine wept during a film about the hardships Jews faced in late 19th century and early 20th century Ukraine because those were her people. I sat in awed silence as two new friends I made in Kyiv told me about their brave participation in the recent Maidan protests. I began praying with more fervor than ever for peace because my heart has become so attached to so many that would be affected if an all-out Russian/Ukrainian war happened.

In Ukraine, for the first time in my life, I felt like I was able to comprehend and handle the widespread depravity and (just as-harmful) apathy that ravages so much of humanity. And this time, it wasn’t nameless, faceless groups, or mentally ill, marginalized individuals that I understood to be a part of this–it’s a seemingly-overwhelming majority.

One of my favorite prophet/poets Josh Garrels sings in his manifesto The Resistance, “How do good men become part of the regime? They don’t believe in resistance.”

I saw that over and again in Ukraine. When no-one spoke for them, an entire people group were nearly extinguished. When no-one spoke up, a country became so corrupt that hundreds of it’s citizens could “disappear” without an alarm sounded. When the nations of the world don’t speak up, a plane full of innocents is shot down. Apathy is perhaps the most destructive attitude in the world. And it is by and far affecting most in the world. Apathy isn’t just a lack of caring–plenty of Americans “care” about civilians dying in Israel and Gaza, or girls kidnapped by terrorists in Nigeria–apathy is a lack of action. Action doesn’t have to be violent. I firmly believe that every person should search and know their souls and if their conscience would allow them to ever take violent action to protect or not. But action is required. And I don’t see that in our world today.

So humanity has lost its sparkle to me. I’ve given up faith in the belief that most people would do something if they knew what was happening. But that doesn’t mean I’ve given up the hope that one by one, that can change. And I have certainly not given up my belief in the essential worth of each human being. In two years, I plan on beginning my masters in International Human Rights, and after that, nothing would please me more than spending every day of my life assisting another worthy human being and convincing them of that worth.

Humanity, I don’t have faith in you anymore. I won’t expect the best from you. But I swear to keep hoping for you to prove me wrong, and to never stop fighting for that.

And hey, if I ever start settling into apathy, someone please shove this post into my face as a stern rebuke

Reblogged this on Musings and commented:

More good words from my friend Anna Maclellan after her time in Ukraine.